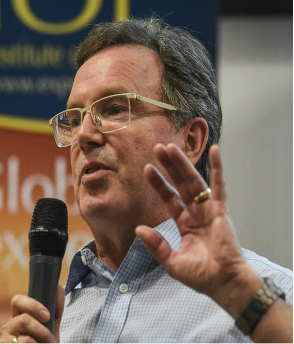

Alastair Ross is a charming, thoughtful man who is more accomplished than he modestly lets on in his brief bio, linked below. Coming from a consultant background, Alastair has a pedigree from 17 years at IBM, which he has parleyed into his own successful consultancy. He’s also written a number of best-selling books – both fiction and non-fiction – and so his advice on authorship in this interview is poignant.

Alastair managed to do what so few founders do; pivot their offering into a sector which was more lucrative and less competitive, and gain traction through reputation and referrals. Read on to find out how he did so.

You can read Alastair’s full biography here

Jamie: Just to begin with, in terms of your career, what have you found most fulfilling?

Alastair: Making positive change to other businesses.

Jamie: Is that true of your current role?

Alastair: Yes, it is. If I look at the satisfying projects, most of my work is about making change, improving businesses and their competitiveness, making them more innovative, and helping them provide better services to their own customers. Seeing that happen and also seeing the capabilities of the people in that organisation improve because of skills transfer; that’s what gives me fulfilment.

Jamie: What do you find most fulfilling about the sales process and the sales aspect to what you do?

Alastair: I’d like to put in a little caveat as I’ve been a consultant throughout my career. As part of my development, I was given some sales training, and hopefully, I’ve been selling all the time, as in influencing people, and particularly in my current business as you have to find work to get work. But I wouldn’t call myself as a salesperson. I would see that as a skill that’s a part of my consulting role.

Jamie: How much of your job currently would you say is spent selling vs delivering?

Alastair: I guess if you blended my marketing activities with my sales activities – because I see them as being very closely linked. My selling model is very much to position myself, and position Codexx well, just like previously at IBM. It has to be a very strong consultative provider to meet a customer or client’s potential needs.

There’s a very important role of positioning your offering. Part of that is providing thought leadership – showing that the organisational design idea; in this case, that Codexx is capable of performing this work. It’s about writing position papers, and running studies with business schools and universities to position your organisation. I used to do similar things at IBM.

We‘re were trying to move into a consulting area where IBM was not strongly known at this time. It was seen very much as an I.T. provider. We were trying to sell business transformation, manufacturing, best practices, and benchmarking. There was a repositioning needed. I think that’s an important aspect in sales; understanding the client, and the company’s business. What is their real pain? What are people prepared to act on?

We’re looking at what does the business need? Is it really ready to act? Because, unfortunately, we waste a lot of time on businesses that would like to talk, but are not ready to act.

About 30% of my time is likely spent on marketing and sales.

If I look back on my career, certainly in Codexx, I’ve either been spending time putting proposals together or meeting with people, but more of the work has been on the marketing side; actually, positioning the organisation, than on just on the selling side.

Jamie: Does that mean that a lot of your sales is done via a tender process or quotation process?

Alastair: I tend not to want to respond to an RFP offering because straightaway there’s always some commoditisation. About 95% of my bids have not been in a competitive situation, as in I’ve developed a personal relationship with somebody in the client. If I look just at Codexx for the last 10 years, I’ve done a lot of work in the legal sector, and that wasn’t really a place where there were a lot of other firms competing, to be honest, because understanding the industry and doing some things that I do is rare. There’s more work from referrals I’ve gained, or they’d seen studies I’d done in this particular area. In those cases, I’m being invited in to talk to them and then it was selling, or rather crafting an offering, which was a fit within their expectations, their abilities, and their budget.

Jamie: How do you evaluate your pipeline for willingness to act to narrow your opportunity list?

Alastair: Sometimes, they are in a nice situation where I get asked to advise them where to start. So, then I’m basically using a consultant’s views and some tools to identify parts of the business where there is more need to act and more readiness to act. If I know some champions there at a senior level that have to do something at an earlier stage, it’s a case of asking some of the questions really – if people are prepared to put the time in, and the senior people in those areas are required to engage with me, then I can see that they’re serious about it.

What are the things that we look at? We obviously know some of the basics, like understanding who actually has access to the budget. Finding out is always difficult, but if you can find out what sort of budget they’re looking at, then you can also find out whether something is possible and a craft your proposal accordingly. It’s always difficult because your clients understand the way it works – when you’re trying to find out that budget, they just see that you’re going to bid according to that budget.

Sometimes – even now – you can get major disconnects. We think we’re on the same page and then you suddenly find out they were thinking about something quite different to what you thought they were thinking. That does happen. But it’s just some of the basic questions – “Is there really a problem there?” or “Is there enough pain to take action?”

These are the sort of things I’ll be asking when I get access.

I want to have a meeting with the key people, whether it’s a senior Partner or a Director or Head of Business, or the Head of the business unit you’re discussing. If you can’t get access to those sorts of people, then it says a lot about their ability or willingness to do something.

Sometimes, you only get discussions at a local level, and these people might help lead you somewhere else, but sometimes they can’t get you any further access. They’re just trying to learn at your expense.

Jamie: How do you deal with that? What strategies do you employ to deal with that level of organisational complexity when you’re selling into these big organisations?

Alastair: I think you’ve got to be practical. Sometimes, you can get seduced. We can all get seduced about a potentially huge piece of work. I’ve had a mixed experience. I’ve got one big industrial client of about 20 years, so I know the people there really well. But when I’m just starting in a new organisation, you have to be realistic. You’re going to think – “We need to learn.” Then, in any case, you can’t start with a vast piece of work with an organisation. They’ve never worked with you before, and particularly if they’re a small business, what I try and do is that I find somewhere where we can start small.

Sometimes, it’s counterintuitive for small pieces of business. What you think is, “If we could get a nice big piece of work there, that’d be great.” But sometimes, that can scare them away or it doesn’t happen and it’s better to find somewhere small to start. We reduce complexity by finding a pilot. We’ll choose one part of the business we’ll start with and find a champion there.

The best way, frankly, of selling internally is showing results. They’ll see a project actually has some impact, and more business leaders want to buy-in, and then you’ll sell them a lot easier. It’s about finding a door that’s slightly open and where they want some help.

Jamie: You talked a little bit earlier about positioning yourself as an expert in the field, and I know you’ve written books that speak to that. Can you tell me a little bit about the importance of positioning yourself as an expert in your chosen niche?

Alastair: I think it’s critical when services can be very easily commoditised.

For example, when I left IBM, I’d done a lot of work in lean methodology, and I had a lot of experience. I came out thinking, “Okay, one of the main services in my new business is going to be lean methodology.” But as soon as I started to look out in the market, there were suddenly so many people providing lean services that the prices were just too low, so I forgot about that. It was only probably about seven or eight years later, I started to get involved in the legal sector, it became quickly clear to me that there are major opportunities for applying Lean methodology. Actually, this would be lean methodology in a different sector where the language is different, the culture is different and therefore, you needed to have that understanding.

I was able to reposition lean in a way that added value for the client, and if other people come from outside the legal profession, they’d get rejected. Because the lawyers would say, “You don’t understand the legal profession.”

When you find a niche like that – a lucrative niche – you need to build on it.

One of the first things I did was starting studies with universities. I’ve got relationships with universities around looking at innovation in the legal sector, for example. Developing something unique, finding partners, because again, you’ve got to think that if you’re trying to be a thought leader, what’s your legitimacy? Why would people believe what you say, rather than what somebody else says? The next year, even without an IBM brand behind you, or a Gartner brand, people still listen to you.

If it’s a small business, they’ll say, “Who the hell is Codexx?” You’ve got to be realistic. By having associations and co-working with some big business schools, you get a brand, and that adds legitimacy to your work. That’s one thing I always try and do, and I think it is important in most cases. I think it’s a bit like having a book. Sometimes, people read them. I mean, I teach it, at some of the business schools like Southampton University and Exeter University, and of course, that helps. But I think generally it reduces the client’s perceived risk, “Yes, we have an expert. He’s written a book.”

Jamie: In terms of getting your name out there, is it important that the book sells or is it more about having information on your expertise available?

Alastair: I think it’s the latter. It’s always nice to have book sales, but if we’re realistic, if you start to add up the number of hours you put into writing a book and divide your sales by your hours, you’ll get very depressed. There lies the madness! Don’t do it. I think in many ways, writing a book is the classic thing you must learn. When you suddenly realise the world and his wife will be pouring over what you’ve written on a piece of digital paper or on actual paper, it does tend to focus the mind to: “I’d better get this right. Is that really true? Why should we believe all these little things?” It forces you to improve your expertise because you’re packaging it in a way that people can look at it and find holes in it.

In many ways it improves your learning. I think if you want to make money, then write fiction.

Jamie: What natural characteristics and what skills are needed to be a successful entrepreneur?

Alastair: I think a bit of naivety helps. I think naivety is very underrated because if you knew all the things that could happen, you would never do anything. Obviously, you need to be thick-skinned. You have to bounce back from failures. You’ve got to be persistent. You’ve got to get out there. You’ve got to talk to people. You can’t conceive the world’s best mousetrap sitting in your office. You need to be out there. You’ve got to be unafraid to blow your own trumpet. I think naturally, I’m more of an introvert than an extrovert. I think being extroverted is a necessary learned behaviour.

Because there’s a lot of stuff available, it’s increasingly difficult to get people’s attention with more and more information out there. You’ve got to be prepared. You can’t expect people to necessarily find their way to your great insights. You’ve got to use the tools out there. You’ve got to be persistent about pushing them out there and advertising, marketing, whatever you need to do. I think you’ve got to be good at recognising when an opportunity comes along, not everything can be planned. If I look at the legal sector, it has been very lucrative for Codexx over the past 10 years. I’d be lying if I said from day one or year one or even year three, I’d planned the legal sector to be a big opportunity for me. I got some work in the sector, and I quickly saw that there were both needs and money, so I modified and developed new offerings accordingly and marketed accordingly.

I think it’s the classic advice – being prepared to pivot your offering when something else comes along. On the other side, that of persistence – I’ve been working on a SaaS offering around supply chain improvement since about 2012. To cut a long story short, I’m now on the fourth iteration with a partner. In some ways, I could have given up a long time ago, but I pivoted each time using some of the “Lean Startup” approaches, and now I have something that looks like we may have some success.

I think the other big thing is working with good people, and this is a good example. My partner in this supply chain offering was my I.T. partner in had another business I had a few years back, he would be the one I’d want to work on this offering with. But by the time I started this project, he was locked up in another business. Now he’s available again, and we’re working together on it. I think that’s the other thing, finding good partners you can work with.

Jamie: Do you have any advice for an entrepreneur or a salesperson looking to start a successful business? What criteria should you use and how should you go about selecting a partner?

Alastair:

As an entrepreneur or in sales, your passion is really important. You’ve got to have that passion. It’s got to be obvious to others. You don’t buy from the salesperson who’s unenthusiastic about their idea. You’ve got to have a passion for convincing others but also keeping yourself going.

You’ve got to have that belief, and I think in partners, it’s finding somebody who shares that passion. I think trust is really important as well. However, I don’t think it’s critical that you necessarily feel like you can have drinks together all the time and be a fantastic friend. That’s always nice; I think that’s sort of icing on the cake, but I think more important is shared passion, shared direction, and trust.

You can’t find that out straight away. But there are a few key things – I think it’s simple things like, if people say they’re going to do something, do they do it? If they can’t do it on little things, why should they deliver on big things? I’ve seen a ton of people who look good initially but didn’t deliver, and we actually have different agendas in the end. You live and learn.

Jamie: Talking specifically about management consultancy, what are the biggest challenges to winning business?

Alastair: I suppose the number one challenge is convincing organisations of the value of having an outsider coming in. Some people don’t want to have somebody external coming in to do things. Most scaled businesses, though, will be used to consulting. Then, it’s a case of “why you?” and particularly why you as a small business – quite a few of my clients will usually pick McKinsey. Some McKinsey people are really good, some of them are just average, but they have the brand. I think from the start, competing against existing and incumbent consultants is always difficult. The other thing is that I think it’s very important to try and productise your offering, so people know what they’re actually buying.

“What are we actually getting?” is a good question, because consulting is a non-regulated profession. It’s not like buying an accountant or a legal service where people are regulated. Anybody can start up and claim they’re consultants. So how do you spot the charlatans?

Making it clear that what you’re actually going to get is important, and I try to focus on deliverables. I tend to try and sell as at a fixed fee because again the client’s nightmare is that the estimate is too small and the fees might increase and increase and we will blow the budget. I think managing that stuff fairly by having fixed fees is quite important. I think doing what you say you’re going to do and being straight-talking is also important.

You’ve got to try and get some sort of relationship at a personal level with the decision-maker, or some of the key people who can influence that decision-maker, because it’s that old saying, “People buy people.” It’s very true in consulting, and they’re going to think, “Can they work with you? Do they respect you?” You need to have specific material focused on proprietary offerings – in Codexx, things like benchmarking tools, and unique approaches because otherwise you get commoditised. This is the issue you face if you’re bidding on public sector bids, whereby definition it’s trying to commoditise everything.

Jamie: Would you recommend management consultancy to any person who’s looking to become an entrepreneur?

Alastair: There are quite a few MBA students who think about going into consultancy.

One of the things I talk about with them is the threats to the consulting business model. There is the regulatory threat. But probably the biggest threat that we’ll talk about is digitalisation and A.I.

There’s no doubt that some of the classic consultancy activities of grabbing a lot of the data, analysing it, and making findings, which can be done using tools such as A.I.

That’s going to change consultancy in digital services where the ability to deliver some of these services via technology, rather than having people on the ground all the time, is going to change things, whether it’s a web-based service or whether it’s using some tailored A.I. tool. I think the nature of consulting is going to change. What won’t change is the need to have people to support change. You have to change your organisation, which involves people and a lot of the reasons that change programmes go wrong is that you have to deal with people, culture, and all the soft stuff. So consulting won’t go away, but undoubtedly the model will be different. Overall, I would say yes, it’s an interesting, exciting career, but it will be different.

Jamie: Bringing it back to the sales aspect, have you found that as you’ve gone throughout your career, you have had to sell more?

Alastair: Personally, I suppose my last 10 years at IBM as a senior consultant, as a principal and as a lead principal, my billing hour targets went down, and I was spending more of my time actually selling and supervising engagements, looking to sell big contracts, which were a mix of consulting and I.T. I’m probably spending more time now in Codexx doing the marketing aspects.

I suppose I feel I spend more time marketing and selling now than I used to because at IBM we had the benefits of cross-selling meaning we had good relationships with the account managers who would actually bring in leads when they were talking to I.T. The director recommended we talk to the supply chain director. You get those leads that we don’t get so much in a small business. I certainly am spending more time selling the service, crafting what the proposal is going to be, what the acceptable price is going to be and what terms and conditions I think are acceptable.

Those things, at a big organisation, I wouldn’t usually get involved in. I think the other thing is that sometimes in large organisations though historically you can get these bad behaviours – let’s say where you may be selling something to just get some revenue in and make a target, and it actually isn’t the best thing for the business overall.

You don’t necessarily get the impact of a bad contract if you sell it. Sometimes you do, but not always, in a big organisation. In small organisations, I’ve got to think, “Can we deliver this?” Because if we can’t, I’m going to get penalised, we will upset clients and maybe get paid fewer fees. I think in a small business, you have to think carefully about selling something around the ability to deliver it.

Jamie: When you started spending more time selling, did you look for specific sales training or was it something that happened more organically? It’s an interesting dynamic in consultancy, much like law, that you sort of start selling in the later stages of your career where you wouldn’t have been at first?

Alastair: Yes. That’s very true. It’s still fresh in my memory, my first sales call when I was a junior consultant back at IBM about ’92, and I was too scared to go on my own. I asked a colleague to come with me to see the managing director of an electronics business. It’s good to look back on that because you forget. You think; “How on earth could anybody be worried about it?” But you know you were.

I think looking at the sales role – you can’t call them a client if you can’t sell to them. Building up your confidence in the ability to have a credible discussion with the client is key. I think what I was worried about is whether I knew enough? Was I going to be in a situation I’d ask a stupid question or not understand what the client said? That was me right at the beginning as I developed within consulting.

However, IBM is famed for its sales school. We consultants didn’t have a full sales school but we had about a week sales training in how to deal with tough questions. We also had additional bits of training focused on the sales side later. Not a massive amount, but that together than with how to be a consultant and doing actual projects builds up your confidence. I think you’ve got to have some degree of training. I think there are some natural characteristics which make you better, or apparently better; more confident on your feet and able to have a discussion with a client, because I can think of some of my colleagues who were salespeople – and some of those who were very good salespeople – who are great at generating empathy with the client and getting them to actually talk with them because that’s the most important thing to start with. You don’t have a business conversation if you just don’t like the person or don’t want to give them time.

As a consultant, you’re brought in for your expertise in content. A lot of my colleagues when we started, there’s no doubt they were actually client unfriendly. We had some people who had great expertise, but they were not very good at relating to clients and other people.

You need to need to complement that with salespeople. Not all consultants are going to be good at selling.

That is the reality, and that’s why I think in the consulting business as you go through the organisation, if you can’t show those selling skills, then you’re not going to progress because you’ve got to have the ability to influence.

You don’t have to be selling a contract, but you’ve got to be selling a concept or selling recommendations. That’s really because selling is about influencing. Ultimately, we think of selling as trying to get people to sign a contract, and you’re influencing them to decide that what your offering is better than anybody else’s. It’s the same as you go through in a consulting programme; you’re always influencing, and trying to influence them based on doing the right things, not to try and get them to do something beneficial to you and not beneficial to them because that wouldn’t be a long term success.

Jamie: How did you feel the sales training was with IBM and in the industry generally?

Alastair: I think IBM sales school is great. I would love to do the full sales school. It’s something like about four or five months. Fantastic. Everybody said how good that was because it’s all about the psychology of selling, there’s lots of training, role plays, and things like that. We had it cut down into a week for consultants. I think there was some very good sales training. At IBM, we went through a big transformation in the 90s moving from hardware-based to a services-based business, and there’s a lot of retraining that needed to be done then, because the salespeople were moving to more consultative sales, and that is why we had more consulting involvement. I was selling mixed consulting; I.T. implementation work. Some big programs though; it’s not really the sort of thing you could have your traditional sales guy selling because you’re talking to an operations director and a finance director. They needed to be comfortable in those in these functional areas.

Jamie: How do you get into management consultancy in the first place?

Alastair: When I started, I was in IBM manufacturing. I joined IBM after a Masters in robotics at the Imperial College London. I spent about 6 years developing robotics systems for production, and then I went into manufacturing management. I was a production shift manager for about six months, and then when that came to an end, there was an opportunity to join a new team as part of a management consulting offering in the factory.

We sold some services, and within a year, we got swallowed up into IBM’s new consulting group. I joined because I had a good general experience in best practice manufacturing approaches which we thought we could sell because we had some early lean methodology approaches, and so the idea was to sell them. One of our first big projects was DuPont. Those types of service were sold from the content side, and it sounded interesting, so that’s how I got in consulting. I think it played well to my structured approach to the knowledge and content knowledge, but of course, I’ve moved well away from that manufacturing side, and I am now working in law firms, but the consultative approach and focus on improvement has continued.

Jamie: Nowadays, how would one go about getting into the industry?

Alastair: Well, you really need to join the consulting firms. Typically, they’ll recruit from business schools; I also teach consulting skills to Masters and MBA students at the University of Southampton Business School, and some students take up junior consulting positions – analysts with consulting firms.

That’s generally the way, and you’ll start as an analyst. If you’re in a very small firm, you might have a slightly bigger role. You’ve got to be careful sometimes, a lot of recruitment consultants will say “this is consultancy”, and you join, but you’re at the end of the telephone, and it’s not really consulting. But basically, you’ll join these firms, you’ll go through the training program, and actually start building towards work and take it from there.

Jamie: What advice would you give to aspiring consultants and entrepreneurs?

Alastair: To aspiring consultants, I think it’s a great career because it’s very interesting. You’ll get a lot of experience. I think the other side is that you need to be very flexible. You’ve got to recognise that you need to travel to where the work is, and it’s often unpredictable. You’ll get in some very challenging situations, but ultimately clients are paying a lot of money for you, and you can’t have an off day. You can’t feel bad, you’ve got to perform, so you’re always on stage.

You’re on stage as far as the metrics in both businesses, because if you like your clients, but you’re not billing enough hours, then you’re failing, or you’re billing loads of hours, and the clients hate you, then you’re failing, there’s just a lot of measurement. My advice would be, yes, it’s a fantastic experience but just be aware of the downsides.

For a start, start early before you’ve got a family before you have further commitments, and be prepared to go wherever you need to go.

On entrepreneurship, I got interviewed on being an entrepreneur about nine months ago, but I wouldn’t see myself as a fantastically successful entrepreneur. But I’ve been running a successful business for 17 years, so I suppose it’s better than most. It’s all relative, and I think of some of my colleagues are better entrepreneurs. I think entrepreneurship is for people who like to stretch themselves, like to have ownership, and people like me who find it frustrating in big organisations sometimes.

Sometimes, it’s nice to have control and just do things yourself, whatever you want to do. I think you’ve got to have that passion. I think it’s going to be hard to take a risk. I think you have to think about the risk you’re taking because most businesses fail. So think carefully before you risk your house.

When you look at how technology has massively helped businesses; small businesses now can be very cost-effective and be very professional. I think it’s a great time for starting a business; particularly an information services-related business because you can have an awful lot of impact. It’s just thinking about that value proposition, what is it that you’re doing differently?

Jamie: Is there any sort of training or experience particularly that you’d recommend that aspiring entrepreneurs look for?

Alastair: There are really good books and tools out there. I think one of the first things when I decided to leave IBM and start Codexx; I needed that confidence. I needed to think, am I doing the right thing? Before I left IBM, I spent a couple of months just meeting with people who’d done it, who’d taken the leap because you forget, and you take for granted – in a large organisation, the cheque arrives every month no matter what. That doesn’t happen in your own business, sometimes the cheque doesn’t arrive at all. There is risk, and I think it’s very easy when you’re working in an organisation to think, “Oh I don’t want to take that risk, because nobody’s taking that risk around me; they’re all still here.”

You have to talk to people who have made the jump and find out, learn from them. Not only does that help you avoid some of the obvious pitfalls but also gives you that confidence. I think that’s an important thing to do. You also really have to know that there is really an unmet need out there. Talk to other people you know, bounce ideas off them, and see if you can get your colleagues and friends to believe in what you’re trying to do.

Jamie: If you were starting your career again, what would you do differently?

Alastair: It’s interesting to look back and think of all the energy I had when I was younger. I think I should have done more. When I was in my early 20s, I did a little bit of coding. I’d have liked to have taken more of an opportunity then to start a business, even a small business, even if it’s on the side; I think it’s a great experience.

I would have done something different at University too. I did engineering. I suppose that the benefit of that was just thinking logically about solving problems, which isn’t a bad thing. I think the most important is to do a degree that you’re passionate about, which is what I advise my kids.

Starting a business early, that’s probably all I would have done differently. It’s interesting how things pan out. One of the things that keep people in big organisations, perhaps longer than they should stay is the comfort factor, and being on a big pension. But you’ve got one life. I think you have to try other things.

Jamie: Would you be willing to tell me about a time when you failed to make a sale, but you gained some really valuable knowledge from the experience?

Alastair: An example for Codexx was two situations where we were providing consulting to services businesses. One was a patent attorney business. They were looking for support on a big reengineering project which bid for and didn’t win. I found out later that another consultancy had just bid for a small part of it to get started and they had got accepted. The learning point for me was because I was very busy in other projects, I put a bid together without thinking, and our approach was, “let’s just start really small.” The client was saying, “Yes, we’d like to do the whole thing,” but I really should have listened to my inner guidance which was “start small”. We had never worked with them, and now they were going to place a large piece of work. That was unrealistic. Instead, they started with somebody willing to go small. I think you’ve got to do that.

Another one where I failed, where it’s always difficult, is when sometime you’re bidding to reengineer a particular legal service and they aren’t really familiar with the approach. I spent time talking with the right people, the Head of Commercial and the Managing Partner of the firm. In the end, they decided to do it themselves because I’d helped to educate them. You’ve always got this slight difference, this tension, that, “We need to tell them just enough.” They can see you’ve got expertise, but if you tell them too much, they may want to do it themselves and you’ve got to think how do you make sure you don’t cross that line and just provide free information for them!

Another one – I’ve tried to avoid public sector bids because it’s a classic commoditisation situation. I did actually bid on one public sector piece of work which for multiple councils in the south of England as a reengineering project, which played very well to my strengths. In the end, I lost on cost to a London firm even though it was further away from their normal expertise. This was back in 2008, so work had really dropped off a cliff and firms become much more aggressive on pricing. I couldn’t see how another business could have come in lower! However, these clients, their endpoint was rather vague, and you could easily see that if you were minded to do so, you could promise some support, and then because they didn’t have very clear deliverables, you could end up having extensions, and they would actually want to add this and that, and the total cost will end up far higher than your original bid. I think you just got to recognise that sometimes you may be competing against people who are playing by different rules from you.

My feeling is always that if you can’t get a personal relationship and understanding with people, you really shouldn’t be bidding, and this is the issue with some of these public sector bids.

Jamie: On the flip side of that, could you tell me about a time when you did make a sale, and it shows off all of the skill and knowledge that you’ve gained throughout your career?

Alastair: Well, I’ve had a long term client – a global engineering client – for over 25 years and 2008 came along it was difficult times, and one part of the business was going to move to a variable cost model. They wanted to reengineer some of their key functions, and they had a workshop to bring key people together – a strategic workshop with some managers. They‘ve asked me to come along to present part of it, get involved and so I did that, and there was a discussion around a key major maintenance function. I bid for that work with a couple of colleagues even though that’s not my core focus area. That was a very big win on that project because of the relationships I have and the past experience I’ve had with that client over several years who have seen me do good work. It’s was a very good proposal, even though you could say the content area was not my speciality, but the approach was very collaborative.

We brought in key people who helped provide the content, we provided the change methodology and over two and a half years, the project was very successful – saved the client a lot of money and also provided a better service. I think the lesson there was that good relationship with an organisation doesn’t mean that you can get lazy and actually provide a weak offering just because you’re the incumbent and there’s nobody else bidding.

I knew if we had a good proposal, we’d get the work, but we always continued providing a lot of key discounts for them because I personally hate this business model that says, “As a new customer, you will get a better deal than an existing one,” – as we see in consumer mobile phones. Codexx provides a special discounted rate for long term clients; to recognise their loyalty – and the lower cost of sales – and that’s a good example of how to maintain a great relationship.

[END]